It’s worth remembering that pre-Columbian Native American sites are not the only archaeological sites that we need to record during Phase I surveys. We need to document anything more than fifty years old, and this includes “post-contact” or “historic” sites as well.

In North American archaeology, the terms “post-contact” and “historic” both refer to cultural material created after European contact with the Americas. The term “historic” can generally be used to refer to the cultural material of any society that used writing, because “history” is the study of written documents. The Indigenous people of the United States and Canada did not use writing before the arrival of Europeans; thus they are often called “prehistoric” (however, the Indigenous people of Mexico and Central America, including the Maya and Zapotecs, did use their own writing systems long before European contact). The European colonizers of the Americas left copious written records; thus we call their cultures “historic.”

Historic sites in the United States are usually characterized by European or Euro-American technology. When Europeans made contact with the Americas after 1492, they introduced a material culture almost wholly different from that of the Indigenous people. But it’s important to remember that not all of the people using this material culture were of European descent. Europeans brought enslaved Africans to the Americas and forced them to use elements of European culture. Native Americans also adopted European material culture in various ways. And Asian immigrants on the West Coast also introduced their own material culture, sometimes manifested in the archaeological record as Chinese porcelain or opium tins.

Protohistory

The term “protohistoric” refers to the period during which European material culture was introduced to an area, especially through trade between Native American tribes, but before there was any substantial written record of the area. This time frame varies from one region to the next, as Europeans did not settle the entire North American continent all at once. By 1800 CE, the East Coast of the United States had already been heavily settled by Euro-Americans for quite some time, and these Euro-Americans left plenty of written documents that historians can still study today. But at that same time, the presence of Europeans in the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, and the Great Basin was very scarce. French fur traders traveled through the Western regions, but they didn’t write much down, so the historic record at this time in these places is scant. The Native Americans who lived in these places already had access to European material culture, such as trade beads, metal tools, and domesticated horses, so their lifeways were no longer strictly “pre-Columbian” or “pre-contact.” But the absence of written records in the area makes it difficult to call these lifeways “historic.” So archaeologists use the term “protohistoric” to refer to the transitional period between prehistoric and historic.

If you ever travel through northeastern Wyoming, you might have a chance to visit the Vore Buffalo Jump site, a natural sinkhole in the Red Valley between the Black Hills proper and the Bearlodge Mountains. The Indigenous people of northeastern Wyoming drove herds of bison into the sinkhole during communal hunts, using the same techniques that their ancestors had used for thousands of years, and they butchered the fallen bison with stone tools. The way of life exemplified at the Vore site is hardly distinguishable from that of pre-Columbian times, though the Vore site was only in use from about 1500-1800 CE, well after the arrival of Columbus. During the Seven Years’ War of the mid 18th century, while the Native allies of the British and French were using muskets and metal knives and tomahawks to fight each other on the East Coast, the Indigenous people living far to the west at the Vore site were still hunting and butchering bison the same way that their ancestors had done since ancient times, without the aid of horses or metal tools (there is no evidence for the use of horses or metal tools at the Vore site in particular, but we know that the Lakota brought horses and metal tools to the Black Hills region when they arrived around 1775). Which shows that European material culture did not permeate throughout the entire continent immediately after the arrival of Columbus. If you want to know when historic artifacts were introduced to an area, you need to study the history of the region. Artifacts from the year 1800 CE on the East Coast of the United States are completely different from artifacts you might find in the Great Basin or the Yukon, even if they date to exactly the same year.

Some of you, who may be enthusiasts of Old Norse culture, may be upset that I have not mentioned the arrival of the Norsemen in North America around 1000 CE, nearly five hundred years before Columbus. Norsemen from Greenland were probably the earliest European settlers in the Americas. There is at least one Norse settlement in Canada, at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, and there may other samples of Norse material culture at the Nanook site on Baffin Island. However, their presence in North America was ephemeral and probably had no lasting effect on the history of the Americas. The Indigenous people of eastern Canada do not appear to have adopted Norse material culture in any way. For better or worse, it was the voyage of Columbus in 1492 that would shape the futures of Europe and the Americas, and create the world that we know today.

Historic Artifacts and Features

For those of us who routinely take part in archaeological surveys, we probably won’t find a lot of protohistoric artifacts, but it isn’t impossible. I have seen at least one European trade bead recovered from a newly discovered lithic scatter during a Phase I survey. You might also find metal arrowheads that were cut out of metal pots, or something else exemplifying the meeting of two very different cultures.

But you are very likely to find much more recent historic artifacts, especially those dating to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Remember, anything more than fifty years old is “historic,” and at the time of this writing, that encompasses everything made up until 1974. As you can imagine, artifacts from the 20th century are very, very common. When you find historic sites on your surveys, most of them will date to the late 19th century or sometime in the 20th century.

It is far beyond the scope of this website to provide information about every type of historic artifact. Historic artifacts include a vast assemblage of glass, metal, and ceramics, made by a wide variety of companies and/or individuals, all with their own maker’s marks. And these maker’s marks were constantly changing over the years. I can’t show you every maker’s mark of every brick-maker, glass bottle company, or pottery factory. That information would fill volumes. If you want specific information about the historic artifacts you might find in the field, I can direct you to the Society for Historical Archaeology.

What I can do is provide a brief overview of the most common historic artifacts you can expect to find in the field.

Ceramics

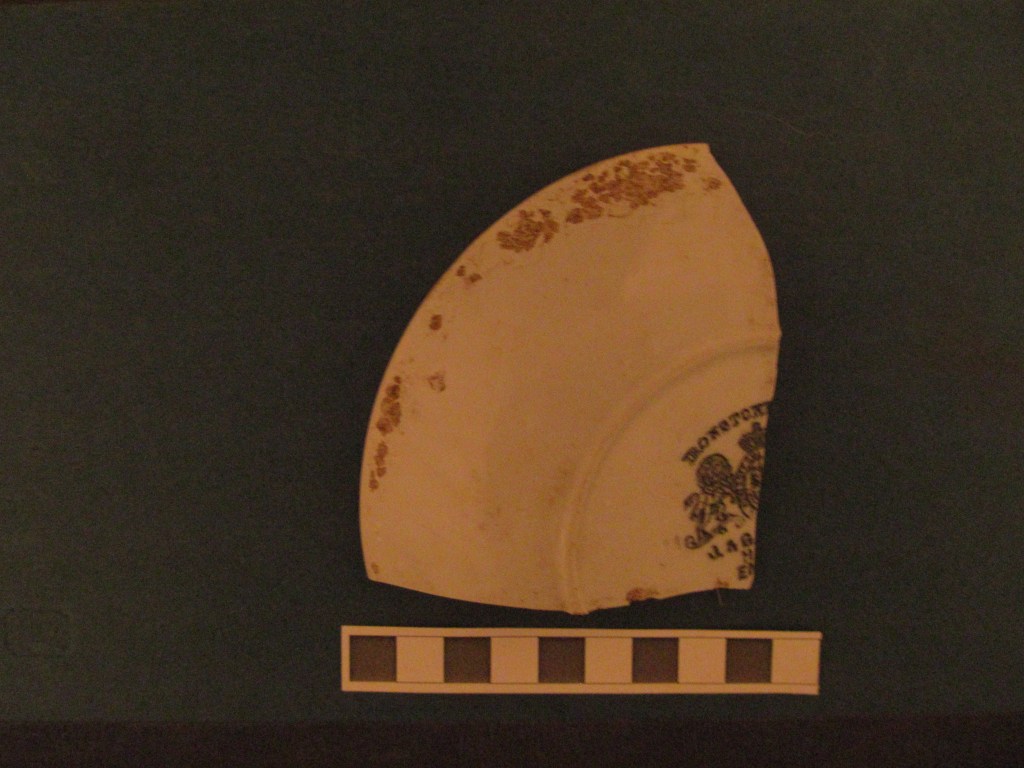

One of the most common historic artifacts you can expect to find, especially if you work east of the Mississippi River, is “whiteware.” Whiteware is simply a term for ceramic dishware with a white glaze (historic pottery, unlike most pre-Columbian pottery, is glazed). For most of the history of the United States, people used tableware—such as plates, bowls, and cups—made from some kind of glazed earthenware. Many of you probably still have similar glazed earthenwares in your china cabinets.

Beginning in the 1740s, English potters began making a type of ceramic dishware with a cream-colored lead glaze; this type of ceramic was known as “creamware.” Creamware was widely used from about 1760 to 1800. Meanwhile, around 1775, another type of ceramic dishware known as “pearlware” became popular (though it was not called pearlware at the time). Pearlware has a blue-tinged glaze caused by the addition of cobalt. It fell out of use around 1840. Around 1820, a new form of ceramic dishware, known simply as “whiteware,” became popular. Whiteware has a white glaze, though it may have some colorful designs painted or transfer printed onto its surface. Whiteware was commonly used throughout the rest of the 19th century and the following 20th century. It is still manufactured today, though many people now eat off of plates made from glass or plastic, rather than ceramics.

If you find a historic farmstead or other habitation site in your survey area, you will most likely encounter copious sherds of whiteware, such as the sample below.

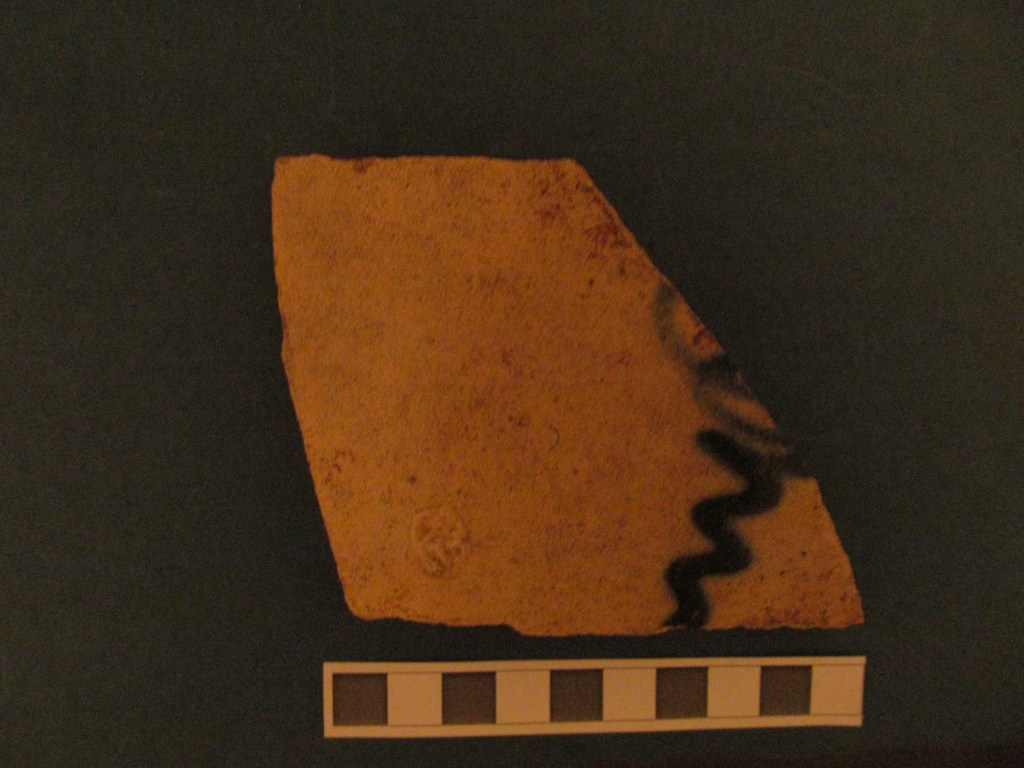

Another common historic artifact that you might find is stoneware. Like whiteware, stoneware is a glazed ceramic. However, stoneware has been fired at a higher temperature than whiteware, and it is generally thicker. Stoneware was often used to make jugs or other storage vessels, rather than tableware. In the days before refrigeration or plastic Tupperware, farmers often stored their food in stoneware jugs, in the root cellars below their houses.

Throughout the 19th century, pottery makers often made “salt-glazed” stoneware, which can be identified by the “orange peel” texture of the glaze. This fell out of fashion by the beginning of the 20th century. Around 1825, pottery makers began putting an “Albany slip” on their stoneware; this type of stoneware was popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and can be identified by its chocolate brown surface. “Bristol-glazed” stoneware was developed as an alternative to salt-glazed stoneware, and became popular in the 20th century. Before 1920, Bristol-glazed stoneware was often made with an Albany slip; after 1920, it was typically made without the slip.

Glass

Europeans had been using glass long before contact with the Americas, and they introduced the art of glass-blowing when they settled in the Western Hemisphere. If you find a glass object in the field, you can be reasonably sure that it is historic rather than prehistoric.

The first glass-blowers in what is now the United States manufactured glass bottles through a process known as “free-blown” manufacturing. This entailed blowing into the molten glass through a long pipe and shaping the vessel by hand, without a mold. This technique was used up until the Civil War (1860s). “Free-blown” vessels can be identified by the lack of any side mold seam on the sides of the bottle.

Later, glass-blowers began to make bottles in molds, and these molds would leave a side mold seam. However, they would use a file to manually grind off the seam along the “finish” (the top of the bottle, where the lip is). And they still blew into the molten glass by mouth. These bottles are called “hand-made” bottles, and they were mostly made between 1820 and 1915.

Finally, glass-blowers began to automate the process with machinery. “Machine-made” bottles can be identified by the presence of a side mold seam that extends all the way to the bottle’s lip, without having been filed off. These bottles were made from about 1900 until the present day.

One sure-fire indicator that a bottle is “historic” is a purple or “amethyst” color. These bottles were originally colorless. Manganese dioxide was added to the glass to remove the colors and make it perfectly clear. But one side effect of the manganese is that it reacts with sunlight and eventually causes the glass to turn purple. This purple glass is known as “solarized” glass. Glass-makers in the United States began using manganese dioxide as a “decolorizing” agent in flat glass around the year 1800, and they were adding manganese dioxide to the glass used for medicine bottles at least as early as 1870. But manganese became mostly obsolete as a decolorizing agent by 1920. Thus, if you find purple glass in the field, you can reasonably place it within that date range.

Beginning around the 1920s, bottle-makers began to emboss “date codes” on their bottle bases. If you find an intact bottle base with a date code, this could let you know the exact year in which the bottle was manufactured. The date code is usually to the right of the company logo on the bottle base, though its placement may vary according to manufacturer. The maker’s mark of the bottle manufacturer can also help you to determine when the bottle was manufactured, if no date code is available. Different companies used different maker’s marks, and these maker’s marks were changed over time.

Aside from date codes and maker’s marks, you can generally be sure that a bottle is “historic” if it bears the words “FEDERAL LAW FORBIDS SALE OR REUSE OF THIS BOTTLE.” From 1935 to 1964, manufacturers of alcohol bottles were required by law to emboss that text onto the glass. Not all manufacturers stopped using that text immediately after the law went out of effect in 1964, and it is known that some manufacturers were still placing this text on their bottles as late as 1974. But by now, even these bottles would be considered “historic.”

Metal

The pre-Columbian inhabitants of North America did not use iron or steel (with the exception of the Inuit), though they did make frequent use of copper (and some of the Indigenous people of South America made bronze). Europeans introduced metallurgical techniques that allowed them to make a variety of tools and other implements out of iron, tin, brass, lead, and various other metals.

One type of metal implement that we frequently find at historic sites is the nail. The earliest nails were hand-forged out of wrought iron by blacksmiths. These nails typically have a square-shaped cross section and a pyramid-shaped head, called a “rose head.” Later, manufacturers used machinery to cut nails out of metal plates. These nails are also square-shaped, but they have flat heads. After the end of the 19th century, manufacturers switched to making the wire nails that we still use today (these have a round cross-section).

In the Western states, historic sites generally consist of scatters of metal cans. In the Eastern states, most people who lived in rural areas before the mid 20th century were farmers who raised a lot of their own food and stored it in stoneware jugs in the root cellars below their houses. But the dry Western climate is not suitable for small-scale farming, and many of the people who moved there became involved with ranching, mining, and felling timber. Cowboys, miners, and lumberjacks often lived in temporary camps and relied heavily on canned food. They left the empty cans scattered on the ground, and these can scatters can still be found today.

Historic Features

During the 19th century, small farmers in the United States often lived in rough cabins built above “root cellars.” A root cellar is simply a large pit in the ground. A wooden floor would be built above this pit, and the farmer and his family would store their food under the floor. Today, root cellars can still be found across the country. Even if the houses above them were destroyed, the pit in the ground is often still visible.

Farmers also built wells and cisterns near their dwellings; these, too, can often be found intact.

Maps and Deeds Research

If you’ve found a historic site, chances are that you will need to conduct some research into the available historic records.

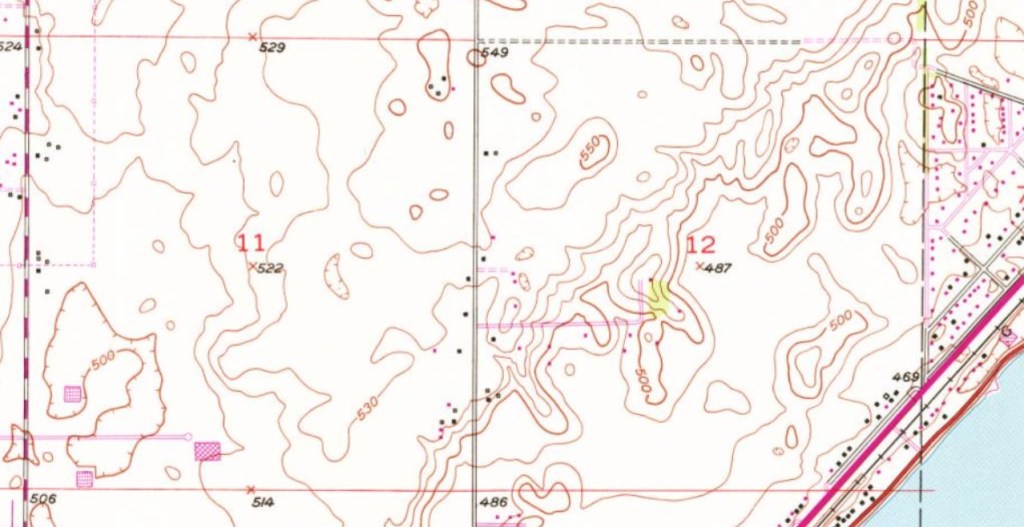

You can start with maps and aerial images. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) began making topographic maps for the contiguous United States in the 1880s, and they continued making these maps throughout the 20th century. The topo maps made at the smallest scales—the 1:24,000 scale, the 1:31,680 scale, and the 1:62,500 scale—show the locations of farmhouses and other structures that the surveyors encountered. These maps will not tell you who owned these structures, but they will let you know if a structure was at a particular spot when the map was made, and that can help you narrow down the age of a site. Historic topographic maps are available here.

Various institutions, including the USGS, began taking aerial photographs of the United States in the 1930s. These were originally taken by plane; now they are taken by satellite. If you see a structure in a historic aerial image, that lets you know a structure was present in the year during which the image was taken. Historical aerial imagery is available here.

If you are researching a historic site that was occupied before the 1880s, the historic USGS topographic maps and aerial images will probably not be of much assistance. Aerial images will certainly not be of any use because they were not taken until the 1930s. Even the historic topographic maps may not be of much use, because the USGS did not get around to mapping many areas at the 1:24,000, 1:31,680, or 1:62,500 scale until the mid 20th century. You may need to look into the plat maps that were drawn by land surveyors in the 19th century. These plat maps show the property boundaries of each parcel, as well as the names of the landowners when the survey took place. They may or may not show the locations of structures on the parcels. General Land Office (GLO) plat maps generally do not show structures, but other plat maps often do.

The Sanborn fire insurance maps are also useful tools for researching the land use history of urban areas. Many archaeological surveys take place in rural areas, but if you happen to be surveying or monitoring in a historic district of a city, the Sanborn maps can help you understand what kinds of structures were originally in the area.

At some point, you will probably have to conduct deeds research on the property where the historic site was found. This means you need to go into the county records to determine the land ownership history of the parcel. This will allow you to know who owned the property when the historic site was occupied. If the property was owned by a historically significant person, that may be a good reason to recommend the site for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). You may be able to access the necessary records through the county clerk’s website online. But not all counties make these records available online, so you may need to go to the county courthouse in person to look through the record books.

To conduct deeds research, whether online or in person at the courthouse, you will need to be able to read legal descriptions of properties. If you are working in a state that uses Public Land Survey System (PLSS), that means you need to understand how properties are designated by township, range, section, and quarter sections. I have already explained how to read and write PLSS legal descriptions in my post about Mapping, GPS, and GIS, which you can access here. That post was meant to teach you how to write legal descriptions on site forms for newly discovered sites, but the same system is used for deeds research.

Closing Thoughts

Many archaeologists working in CRM are reluctant to record historic sites simply because they don’t find them interesting, and they only want to deal with pre-Columbian sites. Other archaeologists prefer historic sites, but they are often disappointed by the relatively recent age of the historic sites that we find during Phase I surveys, which typically date to the late 19th century or the first three quarters of the 20th century. Because these sites are so common, most of them will not be eligible for placement on the NRHP.

But these sites are still an important part of the archaeological record. One of the benefits of archaeology is that it allows us to recover information that was not preserved in our histories, whether written or oral. Sometimes the people who write history are less than honest, and sometimes they don’t fully understand what is happening all around them. Primary sources, valuable though they are, are flawed. Maps and other historic documents are often inaccurate in some way. But at least physical evidence does not lie.

Sources

Archaeology and Collections Branch of the Fairfax County Park Authority. 2017 Creamware, Pearlware and Whiteware. Electronic document, https://cartarchaeology.wordpress.com/2017/02/17/creamware_to_whiteware/.

Lockhart, Bill. 2006 The Color Purple: Dating Solarized Amethyst Container Glass. Historical Archaeology 40(2):45-56.

Nationwide Environmental Title Research, LLC. 2024 Historic Aerials by Netronline. Electronic document, https://www.historicaerials.com/viewer.

Nelson, Lee H. Nail chronology as an aid to dating old buildings. National Park Service.

Society for Historical Archaeology. 2024 Electronic document, https://sha.org/.

United States Geological Survey. 2024 Historical Topo Map Explorer. Electronic document, https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/topomapexplorer/#maps=&loc=-98.54,40.15&LoD=4.00

Leave a comment