I would argue that the most fundamental skill for any archaeological field technician working in the United States is the ability to identify lithics, especially lithic debitage. Below, I will try to explain why. I will also make an effort to teach readers how to identify lithics in the field. However, I would like to emphasize that this blog post on its own will not be sufficient for training readers how to identify flaked stone tools and debitage—in part because the defining characteristics that allow you to identify debitage don’t always show up very well in photographs (which is probably part of the reason that so many lithic analysts prefer illustrations). The best way to become familiar with lithic debitage is to handle thousands of flakes of debitage in person.

Many of you probably have some formal training in lithic analysis, and for you, this blog post will probably not be particularly informative. In fact, it will probably seem oversimplified. But I know that many of you received limited formal instruction in lithic analysis during your college years, and attended a field school at some classical Greek or Roman site before coming back to the United States to work in Cultural Resources Management. Some archaeology students in the U.S. manage to go so far as to get a Master’s degree without ever really learning anything about stone tools, or the Indigenous cultures of the Americas in general. If you fit that description, then this blog post is for you.

Why You Need To Be Able To Identify Lithics

As I have explained elsewhere in this blog, archaeological field technicians in the United States spend most of their time surveying land for previously unrecorded archaeological sites. We have to document all sites containing cultural material more than fifty years old, including both pre-Columbian Native American sites, and historic sites occupied after European contact.

Being able to identify lithics is essential for locating and recording the pre-Columbian Native American sites in your survey area, and to explain why, I’m going to examine the different kinds of cultural material used by ancient Native Americans, and how they are expressed in the archaeological record. More specifically, I’m going to examine lithics, ceramics, copper, and organic materials. Of these four kinds of material, lithics are probably the most commonly found at pre-Columbian sites.

Organic Materials

Most pre-Columbian Native American societies relied heavily on organic materials in their daily lives. They used artifacts made of wood, bark, animal hides, sinews, plant fibers, bone, and shell. Now, most of these organic materials have decomposed entirely, long before they could be recovered by archaeologists. At very rare sites with exceptional preservation, such as at Spiro Mounds, organic remains such as textiles have endured, but I cannot overstate how uncommon this is. Over the course of a routine Phase I survey, field techs will probably not find any pre-Columbian artifacts made from wood, hide, plant fibers, or anything else that decomposes so quickly. If you work in the Southwest, you might encounter some cliff dwellings that still contain the wooden roof timbers, as well as scattered corn cobs or fragments of basketry. But in most of North America, this level of preservation is not possible.

Pieces of bone, tooth, and shell may survive much longer in the archaeological record than most other forms of organic matter, because these organic materials have a mineral component. Human bones and teeth may be present at a burial site. Mollusk shells and vertebrate bones and teeth can also be modified for use as tools. Even specimens that have not been used as tools may be part of the archaeological record if they are affiliated with human activity (these are called ecofacts). The discarded shells of bivalves that were collected and eaten may be preserved in a shell midden, and the bones and teeth of vertebrates that were killed and eaten may be found buried in some kind of pit feature.

These materials survive longer than other organic remains because they are preserved by their mineral component. For example, bones are made of a combination of collagen and calcium apatite (in hydroxyapatite form). Collagen is a protein, and like all proteins, it decomposes over time. Calcium apatite is a mineral. The calcium apatite will protect the bone collagen from decomposition for a little while, even after all the other soft tissues in the body have disappeared, but eventually, even the bone collagen will probably start to decompose. Acidic soils will eventually dissolve the calcium apatite as well. In some environments, a buried human body will decompose completely within one hundred years, bones and all. And bones decompose even more rapidly at the surface.

What this means is that—during routine Phase I surveys—field techs don’t often find bone tools, or any other forms of bone, tooth, or shell that might be part of the archaeological record. At many sites, the bones have simply disappeared, along with all the other organic remains.

Even if you did find an ancient bone during a survey, you would have no way of knowing that it’s part of an archaeological site unless you found artifacts scattered all around it. That is, unless the bone itself has been modified for use as a tool, or unless it is a human bone. I find animal bones on the ground all the time during surveys, but most of these are fewer than ten years old, and even if I found one that was thousands of years old, I would still have no reason to record it unless there were artifacts around it telling me that this bone is affiliated with human activity. Archaeology is the study of humans. Thus, archaeologists have no reason to concern themselves with the bones of non-human animals unless those bones are somehow associated with man-made artifacts or features.

For example, if you find a bunch of animal bones inside a pit feature, you can be sure that those bones are part of the archaeological record because they were placed into a man-made pit. But you’re not likely to find a buried pit feature during the initial survey, because these features are usually not visible from the surface.

Over the course of my career, I have only found one bone tool (though I have found copious faunal remains that were not used as tools, but were still associated with human activity). I barely found any of these faunal remains during Phase I surveys. In fact, most of these were found buried in pit features that I was bisecting and excavating, long after the initial surveys had been completed and the sites had already been discovered.

Then what is the best way to identify a site? The most obvious answer is to look for actual man-made artifacts. Especially artifacts made from materials that do not decompose. These would be the inorganic materials used by pre-Columbian Native Americans: namely, lithics and ceramics (and, in some places, copper).

Lithics

Lithic artifacts are artifacts made from stone. These include flaked stone tools, ground stone tools, and all the lithic debitage (knapping debris) left over by someone producing or sharpening a flaked stone tool. Because these artifacts are made of stone—which is inorganic and does not decompose—they can survive in the archaeological record indefinitely. The production of a flaked stone tool such as a scraper or projectile point will leave behind hundreds of flakes of lithic debitage, making debitage the most common type of lithic artifact. And these flakes have distinctive features (such as a striking platform, bulb of percussion, and negative flake removal scars) that show them to be artifacts, not just naturally broken fragments of rock.

Ceramics and Copper

Ceramic artifacts, such as pottery and tobacco pipes, are made from fired clay. Clay is also an inorganic material that does not decompose, though the moisture in the soil may weaken the potsherds and cause them to crumble. It is very possible that you might find pre-Columbian pottery during a survey, so you need to be able to identify pottery as well. But pottery is generally not as common as debitage. A clay vessel might break into a few dozen sherds, but the process of chipping a nodule of stone into a usable tool will potentially produce hundreds, if not thousands, of flakes of debitage. Even at a site that contains pottery, the flakes of debitage will probably outnumber the pottery.

Furthermore, a lot of sites don’t contain ceramic artifacts. For most of the human history of North America, the Indigenous people here did not use pottery. In the Eastern Woodlands, the Indigenous people did not use pottery until about 1000 BCE, and people in other parts of the continent were not using pottery until much later. The millions of people who lived here before 1000 BCE left countless lithic scatters with no ceramic artifacts, because they simply did not use ceramics at the time.

It is worth noting that many pre-Columbian Native Americans made copper tools as well, particularly in the Great Lakes area. But prehistoric copper tools are not very common outside that region. I have little experience with prehistoric copper artifacts, and am not very well qualified to write about them, other than to mention that they exist.

The Importance of Identifying Lithics

Because flakes of debitage are usually the most common type of artifact found at a site, and because they last forever, it follows that the best way to identify a pre-Columbian site is to notice and identify the debitage. If you’re surveying a plot of land and you come across a pre-Columbian site, regardless of whether you are shovel testing or conducting pedestrian survey, the first artifact that you notice will probably be a flake. Most of the artifacts that you find afterwards will also probably be flakes. The distribution of flakes will probably define the site boundary.

And if you don’t know how to identify flakes, you will walk right over that site without ever realizing it’s a site. In fact, if you don’t know how to identify flakes, you will probably miss every single pre-Columbian archaeological site within your survey area. Which really defeats the purpose of the archaeological survey in the first place. You simply cannot do your job as a field tech if you can’t identify flakes of debitage when you see them.

For the general public, the term “archaeology” probably conjures up images of dinosaurs and lost temples, but the daily reality of life as a field technician is a little different, and arguably a lot more esoteric. We spend a lot of time looking at broken rocks, to see whether they were broken naturally or by human hands. That may seem underwhelming and unexciting, but it is necessary. If we don’t see the flakes, we won’t find the site. And if we don’t find the site, we won’t find all the other things that the site might contain. The site might contain finished stone tools, or buried pit features full of diagnostic artifacts and faunal remains, as well as charcoal that can be carbon-dated. You’ll never have a chance to find that feature if you don’t notice the flakes scattered around it during the initial survey.

Of course, there are some caveats. For one thing, there are places with no naturally occurring toolstone, so the people who lived there had to use stone tools sparingly. For example, on the Gulf Coast of Texas and southern Louisiana, the bedrock is buried deep beneath thick deposits of fluviomarine sediment. The bedrock, and any toolstone within it, would have been completely inaccessible to the Indigenous people living there. As a result, the Indigenous people living in these places did not make a lot of stone tools, and thus did not produce a lot of debitage. For example, the Indigenous people of southern Louisiana made arrowheads from alligator gar scales, rather than flint.

At the Medora mound site in southern Louisiana, an excavation in the 1940s yielded only seven stone tools. Admittedly, there were probably flakes of debitage that were not recorded because archaeologists of the 1940s did not pay much attention to flakes. But a total of only seven stone tools is still a paltry number, especially when compared with the 18,000 sherds of pottery found at the same site.

If you are surveying on the Gulf Coast, you very well may find sites that consist only of shell middens, with no associated lithics or ceramics. You might also find sites with few lithics but a lot of ceramics, such as the Medora site. But in most parts of North America, you can expect debitage to be the most prolific form of artifact at any pre-Columbian site you encounter.

Now, I should add that pre-Columbian Native American sites are not the only sites we encounter during archaeological surveys. We also have to be able to identify and record historic sites. Historic sites usually consist of cultural material associated with Euro-American settlers, though the people who occupied these sites were not necessarily Euro-American. Europeans brought many enslaved Africans to North America, and these enslaved people were generally forced to use cultural material (such as clothing and tools) provided by their enslavers. Native American communities also adopted elements of Euro-American technology over time.

The artifacts found at historic sites generally consist of ceramic dishware and storage vessels (especially whiteware or stoneware), as well as glass, bricks, and fragments of metal. Out west, cans might be more common, because itinerant miners and loggers ate a lot of canned food, while farmers out east raised their own food and kept it in stoneware jugs in their root cellars. Historic artifacts are usually pretty similar to the cultural material that most of us use today. Which makes it easy for most people to recognize historic artifacts as man-made objects.

Here’s a general rule about finding artifacts during archaeological surveys. When it comes to pre-Columbian artifacts, the main difficulty lies in distinguishing man-made artifacts (especially debitage) from naturally broken pieces of rock. If you can’t distinguish a flake from a naturally occurring broken rock, you won’t even realize you’re standing on an archaeological site. But if you are able to determine that the broken rock in your hand is actually a piece of debitage, you can be reasonably sure that this is a pre-Columbian artifact that should be recorded (though there are modern flint knappers who probably leave their flakes on the ground too, and there were even some historic flint knappers who made gun flints for flintlock rifles).

Meanwhile, when it comes to historic artifacts, it is usually easy to determine that these are man-made artifacts. If you are walking across a historic site, regardless of your level of knowledge or training, you will know that the pieces of glass and whiteware at your feet are man-made. The hard part is determining whether they are over fifty years old—and thus “historic” and worthy of being recorded. Obviously, people still use glass and metal and ceramics today, so you need to be able to distinguish historic specimens from modern specimens.

This is why I would argue that it is more important for field techs to be able to identify lithics than historic artifacts, at least when they’re starting out. I’m not saying that prehistoric sites are more important than historic sites. What I am saying is that if an inexperienced field tech is walking over a lithic scatter and does not recognize these pieces of broken rock as artifacts, he or she will miss the site entirely. If that same field tech happens to be walking over a historic scatter, he or she will almost certainly recognize the historic artifacts as man-made. They might not know whether these artifacts are modern or historic, but they can just pick up a sample and show it to their crew chief. And if the artifacts are historic, the site won’t be missed. Meanwhile, if that same field tech is walking over a rocky desert landscape or an agricultural field full of glacial till, they won’t be able to pick up every broken rock and show it to their supervisor to ask if it’s a flake. It simply isn’t feasible. There will be thousands of broken rocks on their transect line. If you don’t know what a flake looks like, you simply won’t be able to do your job at all.

Now, some people probably disagree with my assertion that being able to identify lithics is the most important skill for a field tech. In particular, many Native Americans themselves might tell me that it’s more important for field techs to be able to identify surface features such as cairns or medicine wheels, because these features are sacred. Native American tribal monitors on the Northern Plains take these kinds of surface feature very seriously, but I’ve found that they don’t always care that much about the flakes on the ground. I worked with a tribal monitor in North Dakota who referred to flakes as being “just our trash.” So it would make sense if a Native American elder or tribal monitor got really mad at an archaeologist who managed to record all the lithic scatters within a survey area but missed all the cairns, medicine wheels, and stone circles.

In that sort of situation, maybe identifying lithics shouldn’t be considered our most important skill. But this example is mostly exclusive to the Northern Plains, and field techs in the U.S. have to work in a lot of different regions. And I’ve found that in most regions of the U.S., being able to identify lithic debitage is the most fundamental skill that any field tech must have to do his or her job properly.

I would like to reiterate a point that I made in my Introduction post—that flakes are not the only things we need to be able to notice and identify. Every region has its own unique kinds of cultural material, ranging from the antelope traps of the Great Basin to the cairns and stone circles of the Northern Plains, and you will end up missing something very important if you work in these regions without being familiar with these things.

A Profession Behind The Learning Curve

It’s easy to say that we need to be able to identify lithic debitage. But it’s not always easy in practice. Remember, we are essentially looking at broken rocks to figure out whether they were broken by human hands—or by something else entirely, such as modern farm equipment, or natural thermal spalling. If you phrase it that way to a layperson who knows nothing about archaeology, it probably seems absurd. Maybe even impossible. It’s not impossible, at least not in most cases. But I’ll leave it up to you to decide whether it’s absurd.

Unfortunately, many archaeologists who work in Cultural Resources Management (CRM) are not very good at identifying debitage, even if they are seasoned archaeologists with years of experience. When I was still a field tech, shortly before I went to grad school, I was working with a crew that was surveying an agricultural field beside an old railroad. Some of the railroad ballast had washed out into a swale in the middle of the field. Both of my crew chiefs mistook these chunks of ballast for bifaces (a type of stone tool), and began to record these rocks as a prehistoric site. One of these crew chiefs had eight years of experience; the other had four at the time. While I was still in grad school, I was working with another crew in Ohio. My supervisor, who had seven years of experience, was flagging almost every piece of glacial till or plow-shattered limestone as a prehistoric artifact. Basically, she mistook every piece of rock with a little bit of curvature for a real flake.

Now, I’ve made plenty of mistakes myself. I have misidentified naturally broken pieces of chert as flakes, and I have dismissed actual flakes as naturally broken rocks. I’m sure I will continue to do so. Identifying lithics is not the easiest task in the world, and everybody makes errors. Sometimes there is no way to tell if a broken rock is truly cultural. I will discuss some of the difficulties in identifying debitage in more detail below. But I think there is a level of incompetence that just shouldn’t be acceptable, at least for supervisors.

And CRM archaeology is not great at quality control. A lot of field techs are promoted to crew chief because they know how to use a GPS and they have a very vague idea of what a flake looks like, and it’s assumed that this is all they need to know. The reality is that they end up doing very bad work because they don’t really know what they’re doing, and they are supervising young doe-eyed field techs who also have no idea what they are doing. They end up recording sites that don’t exist while failing to notice sites that do exist.

How To Identify Lithics

People all around the world who relied on stone tools needed to select the appropriate material for their toolstone. They favored types of stone without planes of separation. Typically, they favored chert and obsidian, because these types of stone form conchoidal (or “curved”) fractures when they break. These conchoidal fractures allowed the knapper to make a tool with very sharp edges.

Chert is a type of sedimentary rock made of microscopic particles of quartz (also called “silica,” or silicon dioxide). The word “chert” is sometimes used interchangeably with “flint,” though some sources make a distinction between the two. There is no general consensus regarding the distinction between flint and chert, but some sources classify “flint” as a type of chert. When I speak with laypeople, I usually use the term “flint” when referring to stone tools made of chert, because many people don’t know what chert is. When I speak with other archaeologists, I typically use the term “chert.” Rocks such as chalcedony, agate, and jasper are all very similar to chert, and sometimes impossible to distinguish from chert in the field. These are all sedimentary rocks made of microscopic particles of quartz.

Obsidian is volcanic glass formed from rapidly cooling felsic lava. Like chert, it consists primarily of silicon dioxide.

Freshly broken fragments of chert and obsidian are sharper than any steel, because of the physical properties of these materials. A newly made knife chipped from chert or obsidian is sharper than the sharpest steel knife will ever be. However, chert and obsidian also become dull more quickly than steel knives do, and the only way to sharpen a stone knife is to chip away additional flakes of stone. Chert and obsidian are also more brittle than steel.

People all over the globe made a variety of chipped stone tools by knapping chunks of chert, obsidian, or some other type of stone into the desired shape. This knapping process would leave behind copious flakes of debitage. These flakes have distinctive characteristics that show them to be byproducts of knapping. These distinctive characteristics include:

- The striking platform

- The bulb of percussion

- Cracking ripples

- Flake removal scars

However, it is important to remember that not all flakes will exhibit all of these characteristics. There will be more information in the “Lithic Analysis” section below.

A knapper would typically use some kind of hammer to knock flakes away from a piece of toolstone. This could be a hard hammer—usually in the form of a hammerstone—or a soft hammer made from bone or antler. The place where the hammer strikes the stone is called a “striking platform.” When the hammer strikes the stone, it exerts a force that causes a flake to break off. Sometimes (but not always), the hammer sends a shock through the toolstone in the form of a “Hertzian cone.” If you look closely at the underside of a flake, you might be able to see a Hertzian cone radiating outwards from the point of impact to form a “bulb of percussion.” Beyond the bulb of percussion, the shockwave continues to radiate outwards, forming “cracking ripples” or waves on the underside (or “ventral surface”) of the flake. Not all flakes will have cracking ripples or a true bulb of percussion. But taken together, all these characteristics show that a flake was broken off from the toolstone by an abrupt application of force to a very specific point of impact, forming a shockwave that radiated through the stone. This is not likely to happen if a piece of chert is naturally broken by thermal spalling.

Many flakes have negative flake removal scars on the dorsal surface (or upper side), where previous flakes were broken away. These scars will have the negative version of the recurved shape of the ventral surfaces of the flakes that were already broken off, including the bulbs of percussion. But not all flakes have flake removal scars on their dorsal sides. If you are starting out with a fresh piece of toolstone, the first flake that you knock off will not have the negative scars left by previous flakes. The dorsal surface will be covered in “cortex” (the term for the natural outer rind of a nodule of stone). As the knapping process goes on, the flakes will have less and less cortex on their dorsal sides.

Another characteristic to look out for is called an “eraillure scar.” Sometimes, a small flake will break away from the surface of the bulb of percussion. The flake scar left behind is called an eraillure scar.

Yet another characteristic to look out for is the “lip” that sometimes forms along the striking platform. These lips are generally found on thinning flakes that have been taken off at a late stage in the lithic reduction process.

Not all fragments of debitage will break into pieces that can be definitively identified as flakes, even by a professional. Some break into pieces of shatter that do not exhibit the defining characteristics of debitage.

Additionally, some flakes break into pieces long after the original flint knapping process. They might be struck by a plow, or some kind of construction machinery, and broken into “proximal” and “distal” fragments. The proximal fragment will have the striking platform and bulb of percussion. The distal fragment is the end opposite the striking platform. As you’re shovel testing, you might find the distal fragment of a flake and not recognize it as cultural, because this piece has no bulb of percussion. Your shovel might even be the instrument that broke it.

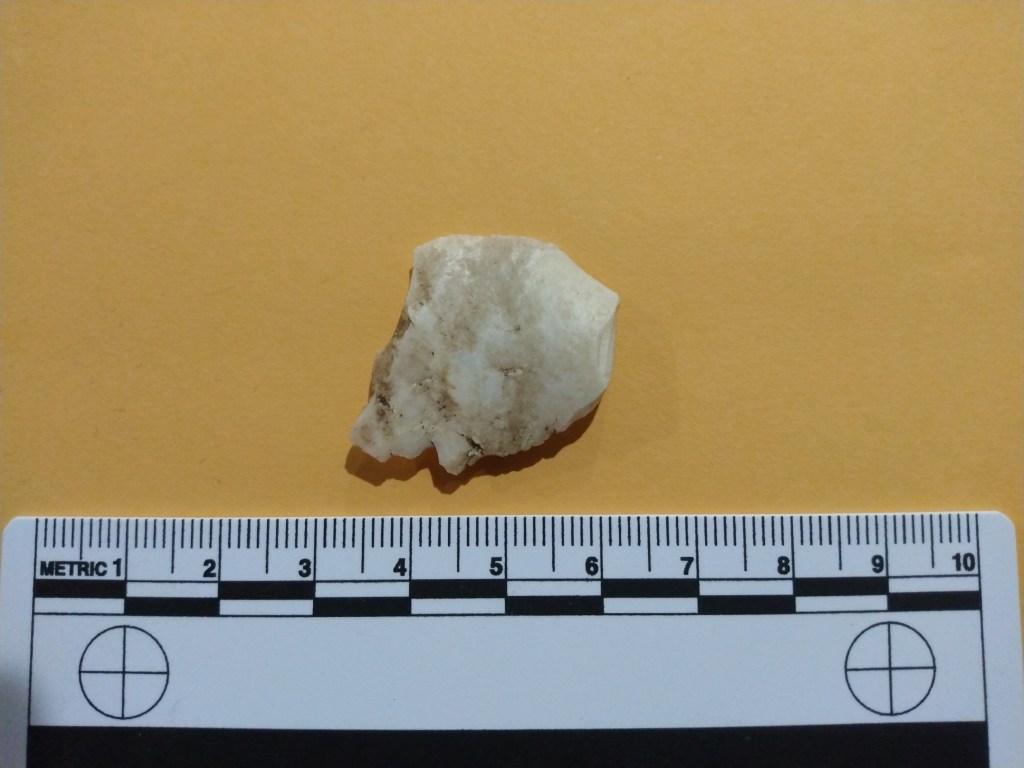

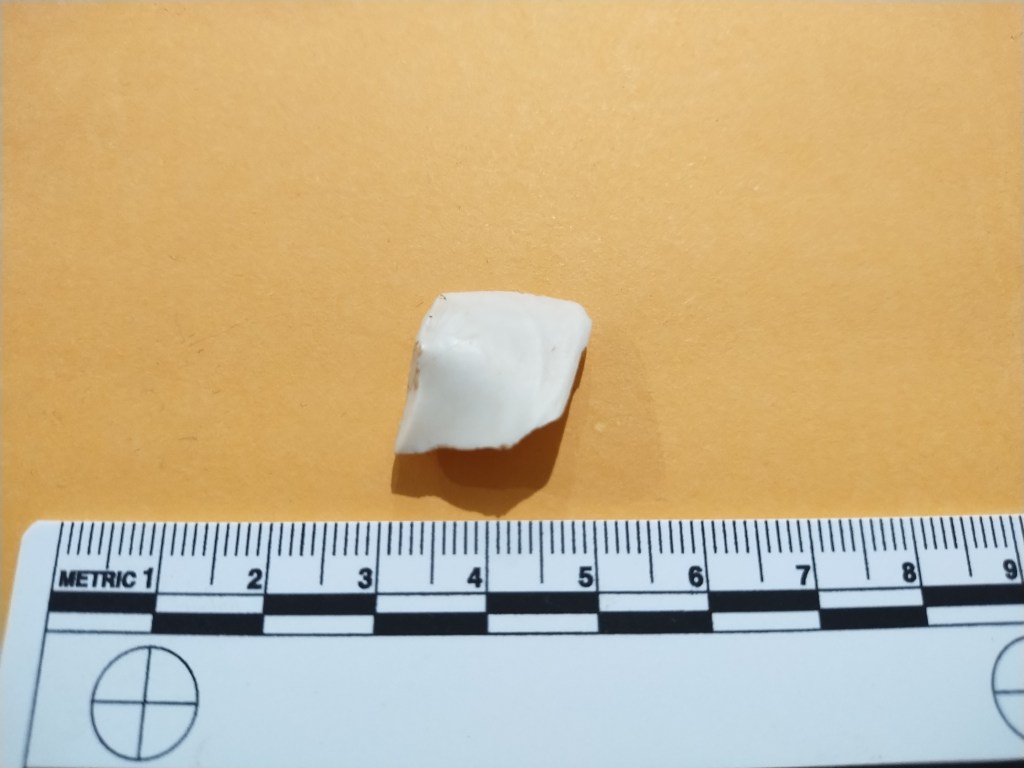

The quality of the toolstone will also determine how easy it is to identify the flakes as being cultural. People generally favored obsidian and chert when they could get it, but these materials are not available everywhere. Pre-Columbian Native Americans also knapped tools out of quartz, quartzite, basalt, rhyolite, shale, petrified wood, porcellanite, and anything else that could possibly form a sharp edge or point. These materials are not as easy to knap, and the tools they make are not of as high quality. Furthermore, it is often difficult to identify the flakes made from these materials.

Quartz is not a desirable knapping material, but it was widely used by the Indigenous people of southeastern Pennsylvania (and many other places), because it was the only local toolstone. Over a decade ago, I was working in southeastern Pennsylvania under the supervision of a lithics specialist. One of my co-workers knapped a projectile point out of quartz and gave the resulting debitage to our boss, the specialist. Our boss analyzed all the quartz debitage and found that he could only identify about ten percent as being definitively cultural. Which means that about ninety percent of the quartz debitage you might find in the field is indistinguishable from naturally broken quartz, even for an expert.

Debitage formed from shale is probably even more difficult to identify as being cultural, because shale breaks along planes of separation, rather than forming conchoidal fractures. But Native Americans made tools out of shale as well, if it was all they had available. Many, many years ago, I was working on an excavation in Virginia, under a different supervisor than the man described above. We were finding little chips of shale, and as far as we could tell, these little chips did not have any of the distinguishing marks of having been knapped (no flake removal scars, no bulbs of percussion, nothing like that). My supervisor was reluctant to record these as artifacts because they did not appear cultural to him. However, the geomorphologist insisted they were artifacts, because we were excavating in a floodplain, and there was no way for those chips of shale to have been deposited naturally in the alluvial sediment. And the geomorphologist was right; these were artifacts. I was also reluctant to record them as artifacts at the time, but now I know better.

And I’ve learned from past mistakes. More recently, I have worked on a massive playa in west Texas, where I encountered big pieces of shale within my survey area. This playa was an ancient lakebed where no fragments of shale of that size could have been deposited naturally. Additionally, these big pieces of shale were surrounded by definitive artifacts, including pottery, and flakes made from chert and obsidian. It was easy to put two and two together and realize these pieces of shale were actually artifacts.

When it comes to lithic materials such as chert or obsidian, it is usually much easier to distinguish actual flakes of debitage from rocks that were broken by natural or mechanical processes. But occasionally there are still difficulties. In places with a lot of naturally occurring chert, I have seen many archaeologists misidentify natural chert spalls or pieces of glacial till as flakes of debitage. Freeze-thaw activity will often cause small pieces of chert to spall off from larger pieces. Changing temperatures cause rocks to expand and contract, leading to tiny cracks. Then, water seeps into the cracks and expands as it freezes, causing pieces of stone to spall off. These fractures are known as “pot lid” fractures (pot lid fractures can occur on real flakes and stone tools that have been exposed to the extreme heat of a fire, but this is also how chert breaks in nature, without any human intervention).

These naturally broken fragments of chert often bear a superficial resemblance to flakes of debitage. They might even have a “dorsal” surface where previous spalls were broken off, and a curved ventral surface where they were separated from a larger piece themselves. But if you look closely, you will probably find that there is no sign of a Hertzian cone forming a true bulb of percussion. And the so-called “flake scars” on the dorsal side don’t show any evidence that flakes with true bulbs of percussion were removed.

Pieces of chert can be broken by mechanical processes as well, and these mechanical processes can also create fragments that superficially resemble flakes or chipped stone tools. Chert that occurs naturally in agricultural fields will often be broken by plows. Just recently, I visited a so-called “site” in a field in central Texas, which supposedly contained several tested cobbles and stone tools. When I arrived, I found that these “tested cobbles” and “stone tools” were all naturally occurring chert nodules that had been probably been chipped by a plow, in addition to being broken by natural thermal spalling.

Also, chert is often quarried and broken into small pieces by heavy machinery, for use as road gravel or railroad ballast. These machines use abrupt force that can send shockwaves through the chert, resulting in fractures with visible Hertzian cones and cracking ripples, which closely resemble the flake removal scars often seen on a flake or a flaked stone tool. I have seen many chunks of chert road gravel or railroad ballast that exhibit cracking ripples on their surfaces. But these were made by machines, not by ancient flint knappers. I have seen many archaeologists misidentify these pieces of gravel as flakes.

All of this is to say that sometimes even an expert can’t tell the difference between a flake of debitage and a naturally broken rock. So naturally, the rest of us are going to make mistakes. And that’s okay. But I think mistakes fall on a spectrum of severity, and mistakes of a certain severity should not be tolerated within CRM archaeology.

Lithic Analysis

For some employers, it may not be sufficient simply to identify flakes as flakes. You may be expected to further classify them according to whichever stage in the lithic reduction process they were made, especially if you plan to leave these artifacts in the field, rather than taking them to a laboratory to be analyzed. Many archaeologists leave artifacts in the field, especially in the Western states.

The problem is that there are different ways of classifying flakes. When I was younger, most of my employers expected me to classify flakes into primary, secondary, and tertiary flakes, based on the amount of cortex on the dorsal surface. The dorsal surface of a primary flake is entirely covered in cortex, a secondary flake is partially covered in cortex, and a tertiary flake has no cortex. But it turns out that this is an imperfect way of classifying flakes, because some flakes that were removed at a very advanced stage in the tool production process may still have some cortex. Some finished tools still have cortex on their surfaces.

Real lithic analysts prefer to classify flakes according to the type of fracture that created them. William Andrefsky, Jr., one of the great authorities on lithic analysis in archaeology, classifies flakes into three main categories:

- Conchoidal flakes

- Bending flakes

- Bipolar/compression flakes

A conchoidal flake is any flake that is “initiated or started by the formation of a Hertzian cone at the point of applied force” (Andrefsky 2005:25). In other words, the crack initiates at the point where the hammerstone strikes the toolstone, and the force of this strike forms a Hertzian cone. The Hertzian cone results in the formation of a bulb of percussion.

Bending flakes are flakes that are “formed by cracks that originate away from the point of applied force” (Andrefsky 2005:28). These fractures do not form Hertzian cones. Strictly speaking, these flakes do not have true bulbs of percussion, at least as defined by Andrefsky. But they often do have a very shallow bulb or “swelling” on the ventral surface near the striking platform. This shallow bulb is often misidentified as a true bulb of percussion by archaeologists in the field (including by me). Because bending flakes do not have a true bulb of percussion, they are generally much flatter and thinner than conchoidal flakes, and they have few—if any—cracking ripples or waves. But they often form a lip along the striking platform, where the flake tears away from the toolstone. Conchoidal flakes may have very small lips along their striking platforms, but the lips found on bending flakes are much more pronounced. According to Mark W. Moore (2024a), bending flakes do not form eraillure scars on their ventral surfaces. However, one experienced knapper has told me that he has often seen small eraillure scars form on bending flakes, especially if those flakes were made from a very brittle material, such as obsisian.

A bipolar flake is a flake that is broken between a hammer and some kind of anvil, so that it has a point of impact on two sides.

Figures 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, and 10 of this blog post show examples of conchoidal flakes. Figure 11 shows an example of a bending flake.

Andrefsky also mentions “pressure flakes,” which are flakes that are broken off by the application of sustained pressure (as with an antler tine or thin piece of bone), rather than being struck off by an abrupt force. But he does not include pressure flakes as one of his three major flake types because he claims that there is no standard definition for a pressure flake. Pressure flakes can be broken off by either conchoidal or bending fractures.

Other lithic analysts will use different terminology to explore very similar concepts. When I was trained in lithic analysis many years ago, I was taught to classify flakes into the following three types:

- Core reduction flakes (also called core flakes)

- Biface thinning flakes

- Pressure flakes

These categories are widely used in publications by authors who are less well known than Andrefsky (for examples, see Gregory Haynes [1996], Chris Ellis [2002], and Albert Pecora [2004], in the sources at the end of this post).

A “core reduction flake” or “core flake” is defined by its lack of a lip along the striking platform, and more importantly by its large bulb of percussion. I’ve known one lithic analyst who distinguishes core reduction flakes from other flake types by placing them on the palm of his hand to see whether their bulbs have the same curvature as his palm. And I’ve known other analysts who do not consider this to be a reputable method. Most would probably agree that a core reduction flake is very similar to what Andrefsky calls a “conchoidal flake,” or at least a conchoidal flake with a pronounced bulb (a conchoidal flake with a very diffuse bulb might be classified as a biface thinning flake).

A “biface thinning flake”—at least according to this classification scheme—is a flake with a shallow or nonexistent bulb, and often a lipped striking platform. This is similar to what Andrefsky calls a “bending flake.” Another attribute that is commonly attributed to biface thinning flakes is a long ridge running along the length of the dorsal surface. However, it should be noted that there are multiple definitions for a “biface thinning flake,” as different authors use different criteria. The analyst who taught me to identify biface thinning flakes described them in a way that is very similar to the way that Andrefsky describes a bending flake, but some authors will also classify some conchoidal flakes as “biface thinning flakes,” if those conchoidal flakes have very diffuse bulbs of percussion (for an example, see Mark Moore [2014]). At the very least, there is a lot of overlap between Andrefsky’s bending flakes and most definitions for a biface thinning flake.

And a “pressure flake,” as already described above, is a flake made by pressure flaking.

Now, some authors make a distinction between “biface thinning flakes” and other kinds of thinning flakes. Some authors will only call a flake a “biface thinning flake” if it has clear evidence that it was removed from a biface, such as flake scars on the striking platform (we would call this a “complex” or “multifaceted” striking platform). If a flake has a shallow bulb and a lip along the striking platform, but it’s not clear that the flake was actually removed from a biface, then these authors will often simply call it a “thinning flake.” These were the instructions I was given for classifying flakes when I was in the Forest Service.

I’m not going to go into much more detail into classifying flakes because I think the classification system really depends on your employer, and whatever source they are using for criteria. But I think it’s important for field techs to understand that different lithic analysts will classify flakes in different ways. Sometimes they use different terms to describe what is essentially the same type of flake, and sometimes they will use the same terms, but with slightly different definitions. Unfortunately, many authors do not clearly define whatever categories they are using in their publications (I am also guilty of this), so there is often a lot of ambiguity regarding these terms and what exactly they mean.

Lithic Materials

In addition to identifying flakes as flakes, and identifying which stage in the lithic reduction process to which they belong, it can also be very useful for field techs to identify the geological material from which a flake (or tool) was made. This is called “Raw Materials Sourcing.”

I’ve already explained that ancient knappers used a variety of lithic materials. They generally favored materials such as obsidian, chert, chalcedony, agate, and jasper, though they were also willing to use less “knappable” stones such as quartz, quartzite, porcellanite, rhyolite, basalt, shale, and petrified wood. Not only can you identify a material as being “chert” or “quartzite” or some other kind of rock, but you can often classify them further as a specific type of chert or other rock that can be traced to a specific geographic area—such as Knife River flint, which occurs naturally in western North Dakota; or Flint Ridge chert, which occurs naturally in eastern Ohio; or Edwards chert, which occurs on the Edwards Plateau in central Texas.

This is very useful information. If you find flakes that were made of a locally available material, that lets you know that the knappers were using toolstone found in the area. However, if you find flakes made of a geological material that can be traced to another region, that means that someone transported that material, possibly over a long distance. Some Indigenous groups, such as those living during the Paleoindian period, were very mobile, so they traveled all over the place, taking pieces of stone with them. Much later, as the Indigenous people adopted agriculture, they became more sedentary, but still made use of far-flung trade networks that could supply them with geological materials (and other resources) from distant lands.

Noticing lithic materials that do not occur naturally in an area can also help you find a site that you might have otherwise missed. Many years ago, I was surveying a field in Ohio and found a shattered piece of “Flint Ridge chert” in a shovel test. This chunk of shatter did not appear cultural at first, but my supervisor and I recognized that this piece of chert could not have occurred there on its own, because Flint Ridge chert does not occur naturally in that specific part of Ohio. We dug radial shovel tests around that piece of shatter and found several definitive flakes, thus confirming our suspicion that the chunk of Flint Ridge chert was cultural after all. Had we tried to conduct that survey with no knowledge of the local geology, we might have missed that site.

There are so many different lithic materials found all across North America, it would take me a decade to compile a resource describing all of them. That is far beyond the scope of this blog. You will simply have to research the geology of whichever area you happen to be surveying. But I’ve included a couple pictures below, that show examples of tools whose specific geological material has been identified.

There is even some ethnographic evidence that Native Americans favored certain geological materials for certain types of tools. According to the Eastern Pomo creation story, as narrated by William Ralganal Benson (1930 [2002]:278), during the first creation of the world, Marumda (the creator deity) “went on and made a mountain of flint: ‘This will be for arrowheads and spearheads.’ And then he went on and made a mountain of drill flint.” The text does not make it clear which mountains in California supplied the flint used for making arrowheads and spearheads, and which mountains supplied flint for making drill points.

The Lithic Reduction Process

Knappers would generally begin with a piece of raw toolstone and chip flakes away from it to form a “core,” which is a term that is generally used for a chunk of rock with flake scars on it. Sometimes, the knapper would continue to chip away at the core until it was reduced to the shape of the desired tool. If this is the kind of core that you find in the field, that means that this core is an example of a tool that was abandoned before it was finished. However, in many cases, the knapper only intended to make a small tool from one of the big flakes chipped away from the surface of the core. Either way, the core is discarded material.

Finished tools could be “bifacial” or “unifacial.” A bifacial tool has been knapped on both sides of the blade, whereas a unifacial tool has only been knapped on one side. Unifacial tools are usually just large flakes that have been modified on one side to form a tool such as a scraper or graver. Bifacial tools would generally include things such as projectile points or drills.

During the production of a bifacial tool, a core—or a large flake taken from a core—could be further chipped away to create a “preform.” A preform is a somewhat nebulously defined term that refers to a triangular or ovate piece that has been flaked on both sides, but is still less refined than a finished tool. I say that the terminology is somewhat nebulous because, according to Shott (2017), “In studies of biface reduction, no consistent vocabulary of relevant terms has evolved.” But most archaeologists can agree that a “preform” is gradually reduced to form a finished tool, while both the preform and finished tool would be considered “bifacial.”

While putting the finishing touches on a tool, the knapper would often resort to a technique called “pressure flaking,” which I have described while discussing pressure flakes in the “Lithic Analysis” section above. The knapper would apply pressure to the edges of the tool with a thin piece of bone or antler tine, thereby forcing off tiny flakes. We know how pressure flaking works, not only from experimental archaeology, but also from the historic and ethnographic record.

Reverend Edward “Tsaka’kasakic” Goodbird, a Hidatsa minister living in North Dakota in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was taught how the older generations of his tribe had used pressure flaking to create stone tools (though he did not use the term “pressure flaking” at the time). According to the Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota (1906:475), “Among the Fort Berthold Indians, Mandans and Hidatsas, old men yet remember when flint was in general use. ‘My father,’ said Edward Good-Bird, ‘told me how he had seen old men make flint arrowheads. They put a skin (pad) in their hand, laid the flint on it, and pressed at it with a piece of bone. He said that the best flint came from deep under the ground.’”

Finished tools became dull quickly, and needed to be sharpened. The knapper would sharpen the tool by taking off additional flakes to create a new edge. This necessarily made the tool smaller; it also created a steeper bevel. A knapper could only sharpen a tool so many times before the tool became too small, and the bevel too steep, for any additional flaking along the edge. At this point, the tool would probably be discarded, though it might be modified to form a different kind of tool, like a drill.

The flakes of debitage left over from making a tool can also be used as expedient tools themselves. These include “utilized flakes,” which might be identified by the polish or use-wear on their cutting edges. They would also include “retouched flakes,” which are just flakes that have been knapped a little along the edges to form a new cutting surface.

This may not seem like relevant information while trying to identify flakes in the field, but modern knappers have found that it can be easier to knap stone while it is wet. The ethnographic record also provides some evidence that knappers would moisten their flint before working it, by putting it in their mouths.

According to Benson’s (1930 [2002]:288) narration of the third creation of the world, “Then he [Marumda, the creator] went and brought back some flint. He warmed it in his mouth and chipped it and made arrowheads.“

Finished Tools

If you are lucky, you might find more than just flakes of debitage during a survey; you might find the finished tools themselves. In that case, it would be useful to learn a little about the different types of tools made and used by pre-Columbian Indigenous people.

1. Unifacial Tools

Unifaces are modified flakes that have been knapped on one side to form some kind of formal tool. These include scrapers, which might have been used for tasks such as scraping the fat and hair from animal hides, or possibly scraping wood. And gravers, which were probably used for making punctures or engravings in a softer material, such as leather or bone. It might not be possible to know whether a flake was used as a graver without performing use-wear analysis, but if you find a flake that was pressure flaked to form a sharp point on one or more sides, that’s a good indicator that you have found a graver.

Some examples of unifacial tools are shown below. These include three scrapers and a graver. All are examples of modified flakes that have been knapped on only one side.

2. Bifacial Tools

A biface is any tool that has been flaked on both sides of the blade. Almost all projectile points, drills, and hoes are bifacial.

a. Projectile Points

Projectile points are often known colloquially as “arrowheads” by laypeople, but most were not hafted to arrow shafts at all. Many projectile points are actually dart points that were made to be hafted to a type of light throwing spear known as an “atlatl dart.” An atlatl dart would be very small and thin, often made from some kind of light material such as river cane. It would probably be fletched like an arrow, to add stability during flight. And it would be thrown with the aid of a spear-thrower or “atlatl” (known in Australia as a “woomera”). The atlatl is a stick with a notch at one end, where the butt of the dart would be fitted. The thrower would use the atlatl as an extension of his or her arm, and the atlatl would provide extra leverage, allowing the dart to be thrown farther than would otherwise be possible.

The use of the atlatl dart precedes the use of the bow and arrow in North America. The bow and arrow was not widely used until about 700 CE, but it did not completely replace the atlatl dart. The Aztecs of central Mexico—from whom we have the word atlatl itself—continued to use atlatl darts alongside the bow and arrow up until the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. In the Great Lakes area, the Ojibwe people still remember their own word for the atlatl—apaginaatig—while using atlatls to throw darts during their winter games.

Below are two examples of projectile points that, based on their size, were probably used as atlatl dart points.

Arrow points are typically smaller than dart points, as they were made to be fitted to arrow shafts. They are often known colloquially as “bird points,” due to the misconception that they were mainly used to hunt birds (these points could be used to hunt any type of game). The Haskell projectile point (Figure 5) and Ahumada projectile point (Figure 6) shown earlier on this page are both examples of arrow points. Below is another example.

Projectile points are sometimes also referred to as projectile point/knives (PPKs), due to the fact that many had secondary uses as knives (in addition to being hafted to arrows or darts). Some were probably used solely as knives. Note that the Ahumada arrow point shown in Figure 6 and the Big Sandy Side Notch dart point shown in Figure 23 both have serrated edges. There was probably no reason for the knappers to put serrated edges on these points unless they intended to use them as knives as well. These serrated edges would allow these points to serve the same function as a modern steak knife, in addition to their use as projectiles that might take down an animal.

There is also ethnographic evidence for the use of projectile points as knives. James Paytiamo, a member of the Acoma Pueblo tribe writing in the early 20th century, describes a deer hunting ritual that was practiced by members of his tribe during his boyhood in New Mexico. Paytiamo mentions that the hunters, after killing a deer, would rituallistically pretend to field dress the fallen deer with a stone arrowhead or spearhead, because that was how it had been done in earlier times—even though, by the time Paytiamo was alive, his people were already relying on metal tools for practical purposes. According to Paytiamo (1932 [1950]:45):

“He [the hunter] pulls out of his pocket a flint arrowhead, and, starting from the deer’s neck pretends to cut it. In older days, they really cut with the spear head, instead of knives.”

Paytiamo does not seem to make a distinction between flint arrowheads or spearheads. Perhaps that is because, by the time of his writing, these stone tools were only used for ritual purposes.

Projectile point/knives are particularly important for archaeologists because they are diagnostic, meaning they can be attributed to a certain time period or culture. There are many different styles—or “types”—of dart point or arrow point, and you can “type” a projectile point by analyzing its size, shape, and flaking pattern. For example, is it stemmed or notched, and if it is notched, is it side-notched or corner-notched? Is the base concave, straight, or convex? Are the edges of the blade excurvate or incurvate? Is the flaking random, or does it have a pattern? Using these criteria, you can assign a projectile point to a specific type. And each type falls within a certain date range, meaning that if you find a projectile point of a certain type at a newly discovered site during an archaeological survey, the typology can help you determine roughly when the site was occupied.

Assuming, of course, that somebody did not find a projectile point that had been made thousands of years earlier and move it to a new site—which is something that is known to have happened occasionally. Below is a quote from Teaching Spirits: Understanding Native American Religious Traditions, discussing how the Lakota would find and re-use projectile points on the Plains:

“The Lakota Sioux, for instance, have a belief that they have never made their own arrowheads out of flint. They find them on the prairie already beautifully made. The belief is that they were made by Iktomi, by the Spider, and this is her offering to the people. As far as I know, I have never met a Lakota who knew how to chip an arrowhead out of flint. They say, ‘Well, we never had to; the Spider did it for us and we find them in little piles on the prairie and we just pick them up (Brown and Cousins 2001:58-59).’”

The ancestors of the Lakota almost certainly knew how to make stone tools at some point in the past. But it appears that, sometime in the historic or protohistoric period, they began to use stone tools they had found on the prairie rather than making their own. It’s clear that the historic Lakota collected some stone projectile points that had been made in earlier times and relocated them to their own camps. If an archaeologist came upon this camp later, he or she might erroneously assume that the projectile point was made at the same time the later camp was occupied. This is something to think about, especially if you are surveying on the Northern Plains, or any other place where projectile points are easily observable on the surface.

But many projectile points are still clearly in situ—especially those that were found in a buried context. It certainly isn’t a waste of time to determine a projectile point’s type, and often, this can still indicate the age of the site at which you found it. This is useful information, and the presence of projectile points (or any other diagnostic artifact) may help to qualify a site for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).

You don’t even need to find a complete projectile point to assign it a type. If you find the base of a point, that is typically sufficient to identify it. Below are a couple of examples.

Sometimes, broken projectile points were reused as scrapers. Unlike most scrapers, these would be bifacial. Below is an example.

The names of these individual types are usually derived from local place-names, near the site where the type was first described. These place-names are often Euro-American in origin. Which means that archaeologists generally use European names to refer to these artifacts, rather than the names that would have originally been applied to them in various Native languages.

There have been attempts to decolonize archaeology by replacing these European names with words from Indigenous languages. However, there is some nuance here that needs to be addressed. Archaeology is the study of gradual changes in material culture over time, such as the gradual changes in styles of pottery or projectile points over the centuries. The histories that most peoples preserve regarding their own past, whether written or oral, generally do not preserve this kind of information very well. Most people who write history, or pass it down orally as a community elder, generally concern themselves with important individuals or events, such as great leaders, battles, or natural disasters. They generally do not say much about miniscule changes in pottery or spearheads over the course of a thousand years, and in fact, I don’t think most cultures around the world have historically been aware of these slow changes in material culture. Most vernaculars don’t even have vocabulary for all the different styles of artifact made and used by the ancestors of the people using those vernaculars as their daily languages. That’s why archaeologists often have to invent terminology for these different styles.

Archaeologists have to invent new terminology to refer to these different styles, even when discussing the material culture of their own ancestors. The Norwegian archaeologist Jan Petersen had to invent new terminology for classifying Viking swords by morphology, because the Vikings who actually made and used these swords did not have language to distinguish between all these different morphologies (or if they did, that specialized language has not survived).

This might be included in a broader discussion in anthropology, about “emic” vs. “etic” concepts. Anthropologists use the term “emic” to refer to a concept that is actually used by the culture being studied, whereas “etic” refers to a concept invented by outsiders (the anthropologists) and applied to that culture. The typology by which we classify projectile points into different types is what anthropologists call “etic.” These are categories that archaeologists have invented themselves. The people actually making the projectile points may or may not have applied similar categories to their own creations.

Which means, if you find something that an archaeologist calls a “Haskell point” or a “Thebes point” or any of the hundreds of other projectile point “types,” not only are you using a word that would have been unfamiliar to the knapper actually crafting the point, but the very criteria by which you are classifying that point into that “type” may not have had any relevance to the way in which the knapper thought about and classified the point in his or her own head. The knapper may not have had any language to distinguish what we call a “Haskell point” from a similar “Harrell” or “Washita” point, and may not have made a distinction between these categories at all.

This may seem very theoretical, and thus removed from the everyday tasks of the average field tech. But I think this kind of theoretical thinking has some value in the field. If you think about projectile points this way, you realize that they don’t have to fit into the “types” or other categories we have in our own minds. A young knapper was probably not setting out to create what we now call a “Haskell” point, with our modern classification scheme in mind. They were probably just trying to make a tool the way they they were taught by their elders, and as a result, their tools adopted a similar style. Thus, projectile points made in the same place and time will tend to look fairly similar, but they will change over the generations.

I will leave it to the reader to decide whether it is best to take an emic or etic approach to anthropology, and whether modern projectile point typology has any value. I believe it does. In my opinion, the great strength of archaeology is that it allows us to reconstruct those parts of our history that our storytellers have forgotten. But I don’t think this should take priority over the ways in which Indigenous elders tell their own history. Ultimately, I believe that the decolonization of archaeology is a wise route to take, but I don’t want to throw away the achievements already made by archaeologists.

b. Drills

Aside from projectile point/knives, another form of bifacial tool is the “drill.” A drill would typically be hafted to a narrow shaft and rotated swiftly (often with the aid of a bowstring), allowing the stone point to bore through a softer material, such as wood, bone, or a softer type of stone. Some Indigenous people drilled holes through pieces of slate or other flat stones to create gorgets or pendants. Sometimes, a projectile point would be re-sharpened so much that it became narrow enough to use as a drill. Strictly speaking, drills are not usually diagnostic. But if you can determine what kind of projectile point a drill originally was, that might help you determine its age.

Below is an example of the base of a drill.

c. Other Bifacial Tools and Miscellaneous Chipped Stone Artifacts

Other bifacial tools and flaked stone artifacts might be localized to a specific region. For example, the members of the Mississippian culture of the American Southeast and Midwest often made flaked stone hoe blades for cultivating maize and other crops, and you might find these hoes if you are surveying in these regions. Meanwhile, The Plains Villagers farther west generally did not make stone hoes, preferring to fashion their farming tools out of bison bones and horn cores. But the Plains Villagers made beveled knives out of stone, for the purpose of processing bison carcasses (see the beveled knife made from Alibates flint in Figure 16). These beveled knives were not very common among the Mississippians.

Beyond the United States, the ancient Maya created works of flaked stone artwork known as “eccentrics.” To the best of my knowledge, eccentrics such as these are not found in the United States, but archaeologists who conduct fieldwork in Mexico and Central America might find them.

Ground Stone Tools and Other Lithics

So far, this post has been focused entirely on flaked stone tools and the debitage left over from their production. But not all stone tools were produced by knapping. Many were made by pecking and grinding. These are known as ground stone tools.

Ground stone tools include bannerstones, pitted stones/cobbles, celts, grooved mauls, and the manos and metates used for grinding seeds into flour. You might also find bedrock mortars, which are surface features that manifest as shallow depressions in the bedrock where someone was grinding corn. Chunkey stones are also ground stone artifacts, but I would hesitate to call them “tools.” They were used for playing a game called “Chunkey.”

Below is a celt, a type of polished stone adze that may have been used for scraping wood. Experimental archaeologists have used celts to fashion dugout canoes out of tree trunks.

And here is a fragment of a metate, a ground stone tool that was probably used for processing plant matter of some kind. It can be identified as a ground stone tool by touch, as one surface has been worn unnaturally smooth.

Also, you may find the hammerstones that were used during the lithic reduction process. These are not exactly flaked stone or ground stone tools. A hammerstone is usually a cobble of some kind of hard stone, covered in pockmarks where it was used to strike a piece of flint.

Closing Thoughts

The identification of stone tools and debitage is arguably the most important skill for a burgeoning young field tech, but field techs should not fall into the trap of assuming this is all they need to know. As I mentioned in the Introduction to this website, field archaeologists should be able to recognize and identify all the cultural material within their survey areas—from the stone circles of the Northern Plains to the burned caliche concentrations and burned rock middens of west Texas, from the earthen mounds of the Eastern Woodlands to the antelope traps of the Great Basin. Identifying lithics is a good foundation, but it is by no means the only necessary skill.

Sources

Andrefsky Jr., William. 2005 Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis. Second Edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Archaeology and Collections Branch of the Fairfax County Park Authority. 2019 Lithic Flakes. Electronic document, https://cartarchaeology.wordpress.com/2019/01/19/lithic-flakes/.

Benson, William Ralganal and Jaime de Angulo. 1930 [2002] Creation. In Surviving through the Days: A California Indian Reader, edited by Herbert W. Luthin. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Brown, Joseph Epes and Emily Cousins. 2001 Teaching Spirits: Understanding Native American Religious Traditions 1st Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ellis, Chris. 2004. The Hi-Lo Component at the Welke-Tonkonah Site, Area C. Kewa 04(5): 1-19.

Haynes, Gregory M. 1996 Evaluating flake assemblages and stone tool distributions at a large Western Stemmed Tradition site near Yucca Mountain, Nevada. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology: 104-130.

Hranicky, Wm Jack. 2015 North American Projectile Points. AuthorHouse, Bloomington.

Moore, Mark W. 2014 Bifacial Flintknapping in the Northwest Kimberley, Western Australia. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 22.

Moore, Mark W. 2024a Stone Tool Analysis: Bending initiation. Museum of Stone Tools. Electronic document, https://stonetoolsmuseum.com/analysis/bending-initiations/#:~:text=Bend%2Dinitiated%20fractures%20can%20also,initiates%20in%20that%20stress%20zone.

Moore, Mark W. 2024b Stone Tool Analysis: Conchoidal initiation. Museum of Stone Tools. Electronic document, https://stonetoolsmuseum.com/analysis/conchoidal-initiation/#:~:text=A%20Hertzian%20cone%20is%20a,fails%20and%20a%20crack%20starts.

Paytiamo, James. 1932 [1950] Deer Hunting Ritual. In Cry of the Thunderbird: The American Indian’s Own Story. Edited by Charles Hamilton. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. Pp. 43-48.

Pecora III, Albert M. 2002 THE ORGANIZATION OF CHIPPED-STONE TOOL MANUFACTURE AND THE FORMATION OF LTTHIC ASSEMBLAGES. Dissertation. Ohio State University.

Projectile Point Identification Guide Toolstone / Lithic Database. 2024 Electronic document, https://projectilepoints.net/.

Przytarski, Jake. 2023 Ojibwe Winter Games combines cultural history with outdoor fun. The Pine Journal. Electronic document, https://www.pinejournal.com/news/local/ojibwe-winter-games-combines-cultural-history-with-outdoor-fun.

Shott, Michael J. 2017 Stage and continuum approaches in prehistoric biface production: A North American perspective. PLOS One 12(3): e0170947.

State Historical Society of North Dakota. 1906 Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota – Volume 1. Tribune, State Printers and Binders. Bismarck.

Taylor, Jeb. 2006 Projectile Points of the High Plains. Aardvark Global Publishing, United States.

West Baton Rouge Museum. 2024 The Medora Site. Electronic document, https://wbrcouncil.org/948/The-Medora-Site

Leave a comment