For most of the human history of the Americas, the people who lived here were fairly mobile. A hunter-gatherer lifestyle often requires you to move around to different resources as they become available. The downside of such a lifestyle is that it is often difficult to carry your house with you as you go. Which means that the Indigenous people of the Americas, as well as other groups of people around the globe, frequently made use of naturally occurring shelters wherever they could be found.

Arguably, the best naturally occurring shelter is what we call a “rockshelter”—a shallow cave beneath a rock overhang. These overhangs often occur in soft sedimentary rocks such as sandstone and limestone. These are not the deep, dark caverns that many people think of when they hear the word “cave,” with long tunnels stretching for miles through complete blackness, replete with hidden sinkholes. Those caves are difficult and dangerous to explore even with modern battery-powered headlamps and climbing gear. They were generally not considered to be ideal habitations. A “rockshelter” is usually just a shallow cavity in a rock face, shielded from the rain and other elements by an overhanging ledge. The photographs below show fairly typical rockshelters that were used as habitations by Native Americans:

The Value of Rockshelters

Rockshelters have a lot of scientific value to archaeologists, for a few different reasons. For one thing, they were magnets for human habitation (and are still magnets to modern campers and hikers), so they often contain pre-contact archaeological sites. Because rockshelters provide some shelter from the elements, they often have potential for excellent preservation of cultural material, even in regions where such preservation is usually lacking. And the sites found within rockshelters have the potential to be stratified by time period.

Stratified Rockshelters

As I have discussed in the page about geology and shovel testing, most archaeological sites in North America are not stratified. For a site to become stratified, there must be deposition of new geological material (soil particles) during the era of human occupation. The deposition of new geological material buries older artifacts and creates a new surface on which younger artifacts can be left. But this is only possible in a depositional environment, such as a floodplain or sand dune, that is still accumulating sediment while people are living there.

The environments where rockshelters are found are typically rugged upland landforms, especially in hilly or mountainous areas. This sort of environment is generally not conducive to the deposition of new geological material. To put it in very simple terms, hills and mountains are too high to be reached by floodwaters, so there is limited potential for the deposition of alluvial sediment. There is some potential for the deposition of wind-borne sediment on high upland areas, but the dense vegetation of the Appalachian and Ozark Mountains anchors the soil in place and prevents it from being blown away, so there is not much wind-borne sediment in these regions either. In general, there is not much deposition of new sediment on upland landforms in hilly or mountainous regions. The soil that you do find on these upland landforms usually formed in situ from the bedrock.

But rockshelters serve as what S.N. Collcutt (1979) calls “highly efficient sediment traps.” Sediment accumulates on the floors of rockshelters, even when there is no potential for the accretion of sediment on the surrounding countryside. And this accumulation of sediment can lead to the formation of a stratified site.

The sediment on the floor of a rockshelter can either be “endogenous” or “exogenous.” Endogenous sediment is sediment that has originated within the rockshelter itself—often, falling down from the ceiling. Natural weathering causes small particles of rock and pieces of rubble to break away from the overhanging ledge and fall to the floor of the shelter. We call this “rock fall.” These particles will gradually bury artifacts or features left on the floor.

Exogenous sediment is sediment that has originated outside the rockshelter. This might include water-borne rock particles that have been washed down the mountainside, or wind-borne rock particles that have been blown into the shallow cave. These particles accumulate in the rockshelter, and the shelter protects them from being eroded away (as they would be if they were left on an exposed mountainside). This, too, can result in stratification. For example, Gatecliff Rockshelter in Nevada contains deposits up to ten meters thick. These deposits were mostly left by water flowing into the rockshelter. The flowing water carried sediment with it, resulting in clearly defined stratigraphy.

Multiple rockshelters in the Great Basin contain intact deposits of tephra (volcanic ash) left by the eruption of Mount Mazama around 5700 BCE. When the volcano erupted, it blanketed a large swath of the Western states with a layer of ash. But in most upland areas, this layer of ash was eroded away, so it no longer exists as a discrete deposit. The layer of ash was only preserved as a discrete deposit in places where it was quickly buried by subsequent deposits of new sediment from other sources. The depositional environments where this occurred include floodplains and rockshelters. Archaeological excavations in rockshelters have uncovered intact deposits of Mazama ash, and in fact, the dating of the artifacts above and below this layer of volcanic ash has helped us to narrow down the date of the volcano’s eruption.

Preservation Within Rockshelters

Another benefit of rockshelters is that they can preserve cultural material that otherwise would not survive into the archaeological record, such as pictographs and organic remains. Meadowcroft Rockshelter, in particular, is famous for preserving the remains of woven basketry and some wooden artifacts. This is especially significant because Meadowcroft Rockshelter is located in Pennsylvania, which has a humid climate that is not otherwise conducive to the preservation of organic remains (especially organic remains that are 16,000 years old).

Bonneville Estates Rockshelter, as pictured above, has preserved organic plant fibers and faunal remains within its sediment. This may be slightly less impressive, given that this rockshelter is located in a desert. But even in the surrounding desert landscape, these organic remains would not have been preserved had they not been buried somehow.

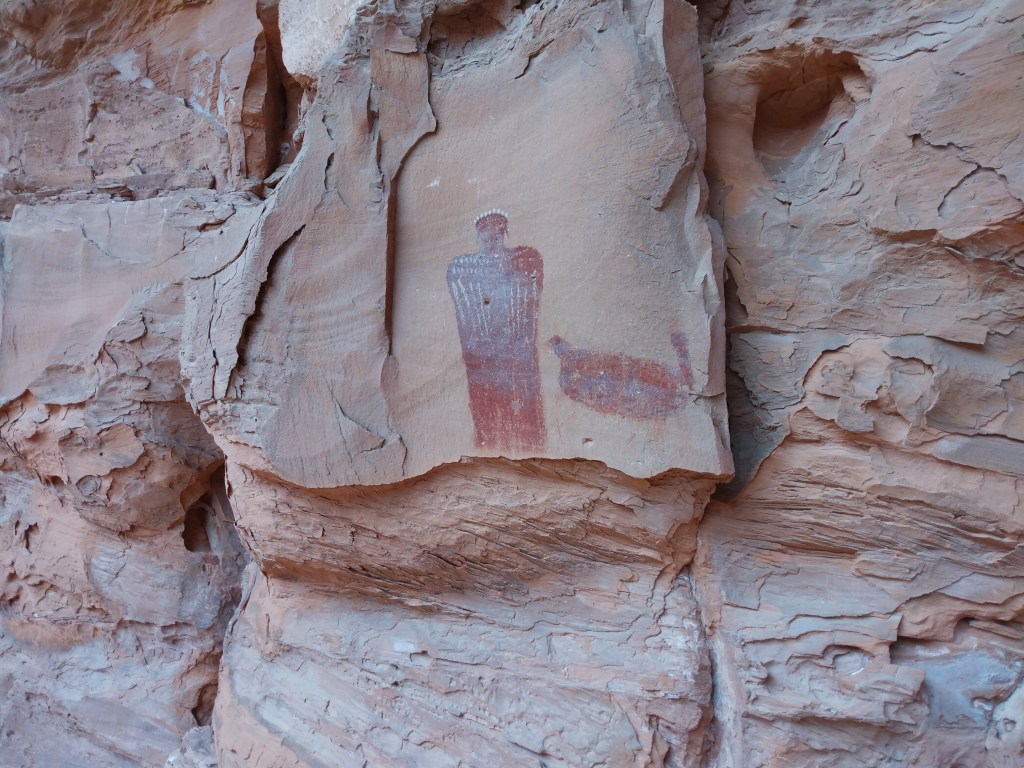

Rockshelters also afford protection to the pictographs and petroglyphs left on the surface of the rock face itself. Pictographs are drawn with some kind of pigment, which might have been washed off by the rain long ago were it not for the shelter provided by the rock overhang. Meanwhile, petroglyphs are carved (or pecked) into the rock face. Because they are carvings, they won’t be washed off the way that pigments are. But they are usually carved into soft rock such as sandstone or limestone, and this soft stone can be easily eroded by the elements. Thus, petroglyphs can be easily eroded away if left exposed, but rockshelters protect them from the elements.

How to Identify Rockshelters

Given the great value of rockshelters, for all the reasons described above, field techs should be serious about locating all the rockshelters within their survey areas. These are often far more informative than the lithic scatters that we typically find in the field.

But how do we identify these as archaeological sites, without causing unnecessary damage to what may be very sensitive cultural material? When I was in the Forest Service, it was standard practice to place a shovel test directly beneath any overhang that we suspected of being a rockshelter. I don’t believe this to be a very wise method. Had these overhangs actually covered archaeological sites, our shovel tests would have potentially disrupted complex stratigraphy and delicate organic remains. It’s probably not a good idea to risk doing so if you can avoid it. I would strongly discourage shovel testing directly in the floor of a rockshelter, even if you’re just trying to figure out if it’s an archaeological site.

The least disruptive method of identifying an archaeological site within a rockshelter is to look for artifacts on the surface. This may be a problem, because the accumulation of sediment on the floor has likely buried all the artifacts and hidden them from view. But artifacts may still be visible along the “dripline.”

When rainwater flows or drips over the edge of a rock overhang, it erodes the soil where it lands. This forms a “dripline”—a line in the ground at the mouth of the cave, where the soil has been washed away. This often exposes previously buried artifacts. If you closely examine the dripline at the mouth of a rockshelter, you can find exposed lithics that indicate the presence of an archaeological site.

A Race Against Time

We should keep in mind that archaeologists are not the only people looking for rockshelters. Looters frequently dig into the floors of rockshelters in pursuit of artifacts that they can sell for profit. Looters are well aware that rockshelters often contain archaeological sites; thus, these rock formations are magnets for looters as well. Unfortunately, I have seldom encountered a rockshelter site with no prior evidence of looting.

The prevalence of looting should give us some impetus to accurately locate and document these rockshelters before they have been completely stripped clean of cultural material. The laws that protect archaeological sites in the United States are not well known by the general public. And laws that are not well known are not often obeyed, or enforced. Aside from the law enforcement officers (LEOs) employed by federal land management agencies, not many police officers even realize it is illegal to dig for artifacts on public land. At times, it seems that archaeologists are fighting a losing battle in the effort to protect these rockshelters.

Perhaps that is our fault. Archaeologists are generally not very good at engaging with the public. Some archaeologists seem to revel in the esoteric nature of our discipline, and they have a tendency to be dismissive or condescending towards laypeople. That creates a couple of problems. For one, the fewer people there are who understand your discipline, the fewer people there are who are able to hold you accountable for your mistakes. I firmly believe that Cultural Resources Management is riddled with poor work, some of it even crossing the line into pseudoscience, and perhaps we would be less able to get away with this bad work if more members of the general public saw it for what it is.

And of course, if laypeople understood archaeology better, they might understand why we try so hard to keep archaeological sites intact and avoid disturbances. If laypeople understood the scientific value of rockshelters with stratified deposits containing preserved basketry, they might not be so eager to dig up rockshelters for recreational purposes. The average meth head who is only collecting artifacts to pay for a drug habit probably won’t care much, but many looters are probably children or ordinary campers who genuinely don’t understand the damage they are causing to sensitive sites. Having a chance to interact with an archaeologist who isn’t a snide asshole might make all the difference.

Sources

Carr, Kurt W. and Roger W. Moeller 2015 First Pennsylvanians: The Archaeology of Native Americans in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg.

Collcutt, S.N. 1979 The Analysis of Quaternary Cave Sediments. World Archaeology 10:290-301.

Farrand, William R. 2001 Archaeological Sediments in Rockshelters and Caves. In Sediments in Archaeological Context, edited by Julie K. Stein and William R. Farrand. The University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City. Pp. 29-66.

Hockett, Bryan S. and Ted Goebel, Kelly E. Graf, and David Rhode. 2021 Prehistoric human response to climate change in the Bonneville basin, western North America: The Bonneville estates Rockshelter radiocarbon chronology. 260(2021):106930.

National Park Service. 1978 National Register of Historic Places Inventory–Nomination Form for Gatecliff Rockshelter (26NY301). Electronic document, https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/1d7c9e75-0bdb-48ca-80ae-4386383f51b7.

Leave a comment